All About Drew

Drew Laney graduated in 1984 from Radford University with a bachelor of arts in music therapy. She is registered and certified with the National Association of Music Therapists and is board-certified by the Certified Board of Music Therapists (CBMT). She has more than 35 years of experience in the field of music therapy, devoting her work to the elderly, children and hospice patients.

Drew has worked with hospitals, nursing homes, hospice care, senior centers, schools, and children’s museums, bringing music, care, and comfort to hundreds of appreciative children and adults.

“When you hear music, it brings back the emotions of the time when you first heard it or when it was your favorite song. It keeps all those memories alive in a way.”

Melinda C.

whose mother Annabel was a music therapy clientQ&A with Drew:

Q: How do you know when you are reaching someone through music therapy?

A: With each person, whether they’re a patient in a hospice, an older adult with Alzheimer’s Disease, or a child suffering with anxiety; beyond conversation, I try to gently engage with eye contact when that’s appropriate. I notice the facial muscles and the body language. I’m looking for engagement and meeting the patient where they are emotionally.

Sometimes I gauge the person’s stress level by their respiratory system. If the person I’m with is in pain and they want me to stay with them, I match the beat of the music I’m playing on the guitar to their breathing. This is the least stressful for the patient and allows me to help lead the respiratory system to a calmer rate (relaxing the muscles can reduce some pain). On other occasions, I’ve been asked by physical therapists to help their patient wake up. It’s very important that by bringing music into the person’s room to wake them up we don’t bring Rolling Stones and yell “hey wake up!’ Meeting the person where they are is almost always the first and best choice. Using rhythm, musical dynamics, music desensitization, and familiar songs, the music therapist helps the patient.

Q: How do you know when you are reaching music students? How is that different or the same?

A: I’m glad you asked. It’s the eyes lighting up and the aha moment. ’I’ve got this musical concept!’, or “I’m creating music!”, or “I’m able to play in sync with this group!”

I do pay attention to how everyone is responding to me and to each other. In a group system, one person having energy can bring up other people in that room. It’s similar because there are therapeutic moments.

Q: Is a music lesson music therapy?

A: I’m glad you asked. Technically, it is not music therapy. It can be therapeutic in the sense of personal growth but I won’t be assessing the students’ emotional needs or keeping information beyond what music we’re working on and what the student wants to learn and seems to enjoy.

Q: Describe how humans’ brains work when we are learning music.

A: When I started out in music therapy, the benefits to the clients were all anecdotal. To get doctors’ referrals, we often invited doctors to come to our groups and see how the patients were engaging and improving. Now there is scientific evidence that shows the value of music therapy. Through MRIs, we can test different portions of the brain and show what is happening when music is being played and or engaged in. There are many areas of the brain being activated in positive and productive ways. I recently saw a study noting that singing has more going on with bundles of neurons than other pieces of music. I find that interesting that that goes back anecdotally to the general picture of the mother singing to the baby- that first human connection. When a person is playing an instrument, it’s totally sensory input.

It used to be that we thought music was working in one hemisphere of the brain. Now, we know it’s both hemispheres being stimulated. The speech area is in the left hemisphere for 97 percent of the population. Let’s take Gabby Giffords (the former Arizona Congresswoman who was shot in the head). That’s not until she began singing using the right hemisphere that she began to speak. Her speech is still not as clear as before the gunshot, but she is continuing to improve.

Q: How do you define music therapy?

A: Music therapy is using music as the tool to enhance what the person needs that is not musical. It’s creating music activities for nonmusical coping skills to manage behavior. These are music activities not for a musical problem, but to help someone talk, communicate with others, relearn how to walk, ….

Music Therapy is also assessing the patient, coming up with appropriate goals and implementing activities to help with those goals. Music Therapists are also responsible for keeping up to date charts on the patients’ progress.

Q: What is your idea of a successful group music lesson?

A: The laughter. That’s very successful to me. My seeing that the music technique is being implemented, and when the group is playing together, there is joy in that, and if the group is experiencing collective effervescence.

Q: What are some of the most profound things your students have said or done during music therapy?

A: I love hearing ‘I really needed this today’, or ‘I have been really looking forward to this week.’

A few years ago I worked with a woman who was working with physical and occupational therapists after a stroke. She signed up for ukulele out of curiosity. By playing the ukulele, she was able to develop strengths in her left hand that complemented what she was working on with her other therapists. Because she enjoyed it so much and became comfortable with the ukulele, she also started singing solos. Her hands, arms, and the muscles around her mouth became stronger along with her vocal cords and self-confidence

One of my other favorite people will always be Mrs. R. She was a survivor of Auschwitz and was living with Alzheimer’s Disease. Her original language was Polish. Before her dementia worsened, she would speak to me in English very comfortably. She was delightful to be with and seemed to enjoy discussing the songs she would like and what I showed her on the ukulele. She told me she always loved music and meant to learn the piano but never got around to it. As the dementia continued to worsen, she didn’t seem to notice whether she was speaking in English or Polish. She expected me to understand both. When I asked her to repeat something in English because she had switched to Polish, she would say, ‘well, you understood me a minute ago!” She also didn’t remember she had played ukulele with me two days before. She explained she couldn’t play and after I got her through songs we both knew, she would shrug her shoulders and grin, and say, “Who knew I was so musical!”

I also like to share the information that shows how music therapists working alongside physical therapists and/or occupational therapists can be beneficial. The appropriate music can improve good outcomes by 50%. It gave me great joy to collaborate with OTs and PTs. Creating the beat to fit the exercises and finding songs the patient would enjoy and find a connection to was a delight. Quite a few patients seemed to enjoy singing “Bill Bailey” with me as I walked backwards in front of them, playing the guitar or a ukulele to keep the steady and most helpful beat, as the PT or OT had their arms around the patient to make sure they had what they needed. After the exercise, the PT or OT almost always exclaimed over how much further the patient was able to go. They said, ‘wow, we got further today than ever before.’ It was a plus that the patient would be laughing and singing as they were following me and didn’t seem to realize how much they were getting done.

“There is always light. If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.”

Poet Amanda Gorman

Q: What musicians do you admire and why?

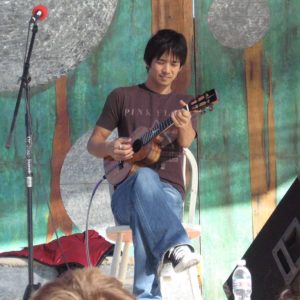

A: Jake Shimabukuro (the talented ukulele performer), because he’s just so joyful. And Ella Fitzgerald. She can do nothing wrong. I’ve enjoyed her style and her collaborative work with

other greats. Her generous spirit, teamwork, and ability to read her fellow musicians is what I strive for in a medical or non-medical scenario.

And Mary Chapin-Carpenter and John Prine, because their music is powerful and from the heart. It’s also of outside the box.

Q: Why did you decide to become a musician and music therapist?

A: I’ve always enjoyed music. Singing was something I understood. It was similar to playing a game and already knowing the rules. The introvert part of me could relax when I knew what was expected. As a child, it was one of the things that connected me with my dad. My mom and two older sisters couldn’t carry a tune so I was encouraged to figure out song lyrics or lead the songs on car trips. At 15 I first became aware of music possibly having healing qualities. On a church retreat in Virginia, my best friend Lainey and I were playing guitar and rehearsing songs for the upcoming worship service. We were surrounded by beautiful trees and near a creek. Between the nature and vocal harmony I realized I felt something lighter than usual. I’m sure it can be explained by the changes in my respiratory system and the endorphins being increased. At the time it felt very nature and God-connected. I didn’t know it then, but I know this connected me to the path of being aware that music, and especially vocal harmony, could surround us and aid in healing.

During most of my childhood and teen years, I shared the bedroom with my sister, Faye, who was four years older. She was an exceptionally lovely person and I felt lucky to be with her. Some evenings and especially when she was feeling stressed, she’d ask me to sing and play the guitar for her. When I was 19 and Faye was just 22 she died from an Addisonian crisis. A couple of months after I quit yelling at God, I started asking, ‘why am I here? It eventually occurred to me that using music to connect with and/or calm Faye was something to look into. I went into music therapy devoted to hospice care. I used music in various ways to aid in communication between the terminally ill patient and their loved ones, ease the physical and emotional pain of the terminally ill patient, and most importantly, aid the patient in feeling comfortably alive until their death.